“Nine for Mortal Men, doomed to die,

One for the Dark Lord on his dark throne

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them,

One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them.

In the Land of Mordor where the Shadows lie.” – J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Lord of the Rings”

An eventful year and decade in the history of cyberspace will be closing soon. Thought I would jot down and comment on what I noticed in those 10 years while working in the area of cybersecurity and defense policy. Examples come from publically available non-classified sources only[1]. Many of us will probably have their own list, which may or may not be similar to mine but am sure were noticed even if they do not place the same weight as I do on them. The list is in no particular order of priority but put down one after the other as they came to me. So let us start:

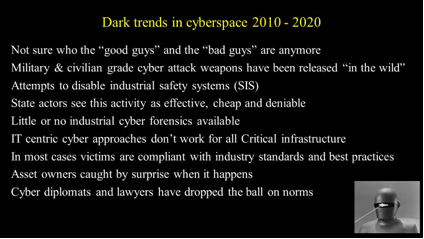

- Not sure who the “good guys” and the “bad guys” are anymore. There is a kind of cyberspace “iron curtain” dividing east and west again. If you live in the West and after an incident it is determined that a state was behind it the culprit state tends to come from a list of “usual suspects” from the East namely Russia, China, N. Korea or Iran. Yes, these states are notorious for their cyberspace misbehavior but no one seems to notice what the other cyber superpowers from the West are doing. Take the alleged attacks by the RF on the US power grid for example[2]. The US also seems to be engaging in similar attacks[3] and against one of the countries on the usual suspect list[4]. Bottom line here is that two countries who put on a face of promoting cyber peace behave completely differently in the shadows of cyberspace. This activity is not being “policed” by the international security policy community and risks spiraling out of control. As we learned during the wars of the 20th Century if the spiraling leads to a “shooting” conflict with critical infrastructure as the target the civilian populations that will suffer the most.

- Military & civilian grade cyber-attack weapons have been released “in the wild”. One of the fears after the fall of the Soviet Union had to do with the large nuclear weapons arsenal the Soviet state had built up. What would happen if during the chaos someone decided to sell some of those weapons to a terrorist or renegade country? Thankfully, at least at the time of this writing, this never seems to have happened. In terms of cyber weapons, we have not been so lucky. The apparent theft of cyber-attack tools (weapons) from a state’s secret cyber program and later distribution on the Internet by the “thieves” had significant repercussions in the form of WannaCry and NotPetya in 2017[5]. This theft was not a single occurrence for it just happened just weeks ago to a civilian cybersecurity company[6].

- Attempts to disable industrial safety systems (SIS). This probably is the darkest of all the trends listed here. It appeared at the beginning of the decade with the Stuxnet operation (which deserves a separate mention on this list) and again with the cyber-attacks on the SIS of a petrochemical facility in 2017[7]. The stakes have been raised by perpetrators who no longer seemed to care if lives and property were lost or damage inflicted to the environment. The perpetrators of the 2017 were not apparently successful (we are still not sure of their actual intention) but either they or copycat actors are encouraged like the early rocket pioneers to keep on trying[8].

- State actors see this activity as effective, cheap and deniable. Not much to add here. The lack of action by the international security policy community to a growing list of malicious cyber activities of states speaks for itself. This is perhaps the most dangerous of all the trends coming out of the past decade. We have seen this kind of response to a clear and present danger before. It was during the rise of the infamous dictators in the 1920’s and 1930’s.

- Little or no industrial cyber forensics available. A good example is the Triton/Trisis case. The victim had a full complement of plant engineers, managers and maintenance personnel and even probably armed guards to safely operate and protect the plant from physical dangers including those posed by the monitored and controlled physical processes in the plant as well as from external attacks from terrorists. However, when it came time to determine the cause of two unscheduled and costly shutdowns the victim had to outsource during a time of crisis cyber forensic experts from other countries[9]. From what I have seen of engineers, this is not an unusual state of affairs. They are too busy keeping things up and running and do not have the time or capability to stop what they are doing to conduct a cyber-forensic investigation on a real-time system. As we look to the next decade, we can expect this weakness to be further exploited.

- IT centric cyber approaches don’t work for all Critical infrastructure. This is looking down on an open can of worms. There is a lot of confusion in terminology to begin with. Most are pretty clear about what IT is since many use it intimately in their offices, homes and in their pockets. However that knowledge falls far short when developing and implementing a policy critical infrastructure protection (CIP). There remains a wide “no mans land” in terms of understanding between the CISO’s and the Senior Plant Engineer[10]. One thinks in terms of protecting information and data while the other is concerned about viewing and controlling a potentially hazardous physical process. A different approach is needed here to supplement the IT centric one. A good starting point is to agree on what IT, OT and ICS are. Both the CISO and the Engineers need to work on this working vocabulary together. At the present time terms like OT, ICS, and SCADA are used to describe the same thing when they are not[11]. If we do not agree on what we are trying to protect before we come up with a protection solution we will be forced to learn the hard way.

- In most cases victims are compliant with industry standards and best practices. Target, Sony Pictures and other enterprises are examples of this in the Office IT environment but it also extends to industrial operations. I have myself listened to a VP of an oil company boast of his companies implementation of ISO 27000 . Maybe his engineers are aware of and use the standards most relevant to the particular physical process they are responsible for monitoring and controlling. However, I have met engineers who put their faith in industrial strength firewalls stationed at the perimeter to protect their internal control networks. When I hear that I remember the words of two military cyber specialists during an cyber exercise “oh, so they have a firewall, which of the 37 ways to breach a firewall should we use?”[12].

- Asset owners caught by surprise when it happens. I do not think I have to look at many published cases when this was not true. I think this is a result of a failure to answer 3 basic security policy creation questions. What to protect? From what threats? and How to protect identified assets from identified threats in the most cost effective way[13]. As in the fable of the “3 Little Pigs” only one of the pigs took the time to analyze and answer those questions. Until that takes place the asset owner has little means to judge the proposed solutions from eager vendors.

- Cyber diplomats and lawyers have dropped the ball on norms. I will put my hand in the hornets’ nest here and risk losing some friends I have made over the years in the international security policy making community. I have put on my “cyber diplomat” hat every now and then over the years and tried to work toward finding a way to manage state misbehavior in cyberspace, at least during peacetime[14]. Many meetings and conferences have taken place and have noticed several features. Concrete proposals that can reduce the threat that states pose to each others cricital infrastructure never get very far. I think this is because the states who have powerful cyber capabilities do not want to see any limits exercised on their rights to use their “toys” when they want to. These people some of them I admit are very capable and well-meaning do not have the ability to comprehend what changed in 2010 with the appearance of Stuxnet. Seeking to agree on states sharing of information about their strategies and laws will do nothing to make the work of the engineers in protecting critical infrastructure any easier. The policy people in their meetings need to invite the engineers and hear what they think of such proposals. Engineers should be willing to accept the invitation. It is in their own best interest since they may find the partnership will make their job easier in the form of rational and coherent policies. At the least it will reduce the already heavy burden of having to run an industrial operation and deal with advanced persistent threat attacks aimed at their backs.

p.s. while writing this I wanted to list a 10th trend. However it is possible to hope for one. In 2018 some noted that it was a 100 years since US President Woodrow Wilson presented his “14 Points” proposal to the Versailles Peace Conference which was to end the “war to end all wars”. In that spirit I have developed a 21st Century cyberspace equivalent,”14 Points for Peace in Cyberspace, which was part of a article I contributed to a recent book on International Law in Cyberspace( ) . Will see if I can later share an excerpt here. Stay tuned.

[1] Pretty sure the classified ones will confirm

[2] https://www.wired.com/story/russian-hackers-us-power-grid-attacks/

[3] https://www.securityweek.com/us-planted-powerful-malware-russias-power-grid-report

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/15/us/politics/trump-cyber-russia-grid.html?auth=login-google

[5] https://www.wired.co.uk/article/what-is-eternal-blue-exploit-vulnerability-patch

[6] https://threatpost.com/fireeye-cyberattack-red-team-security-tools/162056/

[7] http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2018/08/28/targeting-control-and-safety-instrumented-systems-sis-new-escalation-of-cyber-threats-to-critical-energy-infrastructure/

[8] https://threatpost.com/triton-ics-malware-second-victim/143658/

[9] Watch J. Gutmanis’s (Australia) first responder account https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XwSJ8hloGvY

[10] Further discuss this here: http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2020/08/17/is-there-a-problem-with-our-understanding-of-the-terms-it-ot-and-ics-when-seeking-to-protect-critical-infrastructure/

[11] http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2019/02/12/regarding-ot-solutions-coming-from-traditional-it-security-vendors/

[12] http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2019/04/19/impressions-from-a-live-fire-cyber-exercise-relevant-to-ics-security/

[13] http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2018/02/21/towards-cyber-safe-critical-infrastructure-answering-3-questions/

[14] http://scadamag.infracritical.com/index.php/2020/10/16/tale-of-two-conferences-on-protecting-critical-infrastructure-it-was-the-best-of-times-it-was-the-worst-of-times/